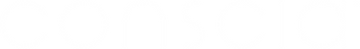

Schizonema comoides (top left), Conferva Linum (top right), and Callithamnion pedicellatum (bottom) Callithamnion pedicellatum from Part XI of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1849-1850

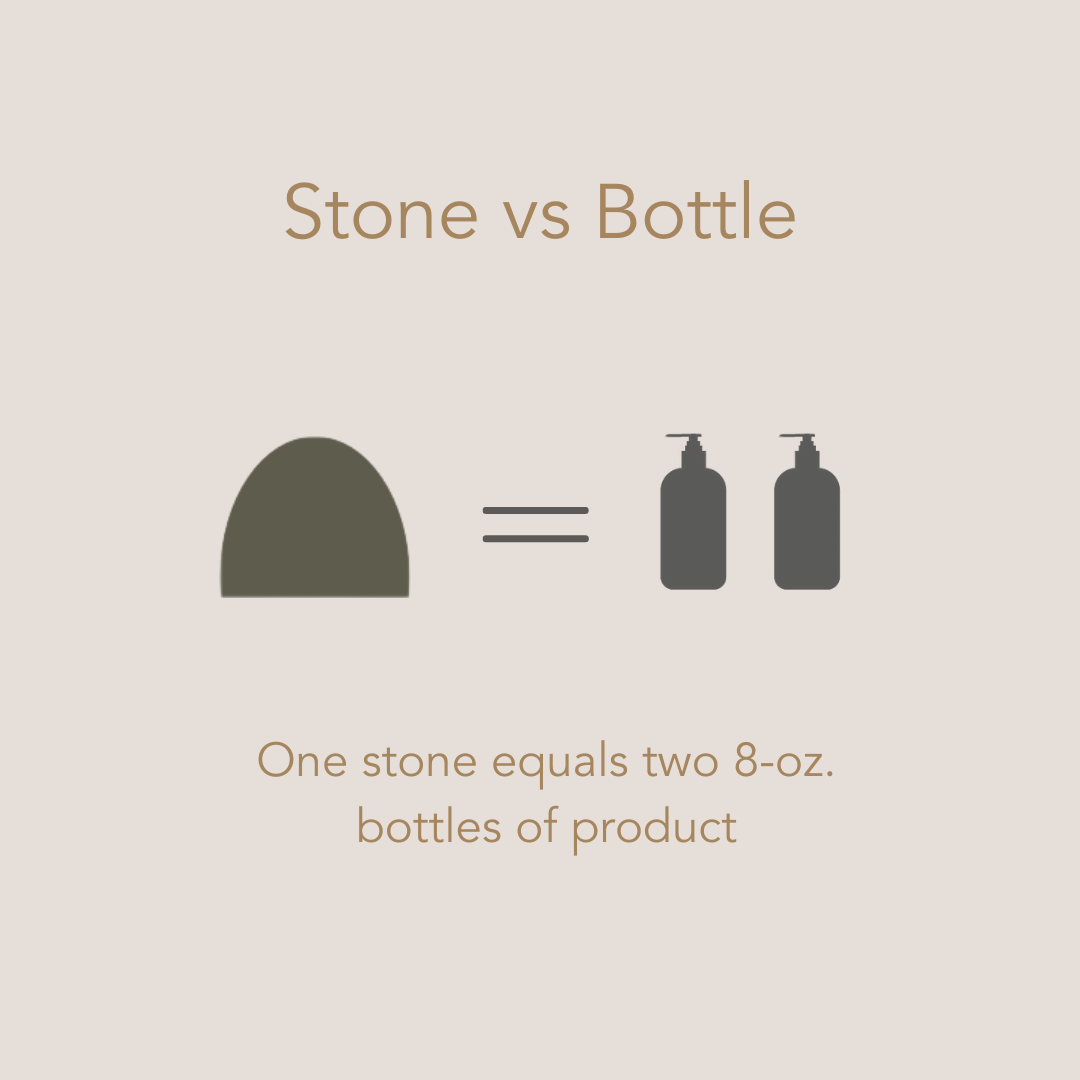

While her aim wasn’t to be an artist, Atkins was clearly tuned into aesthetics, laying her subjects out on the page in choreographed compositions, from groupings of small sprigs to singular tentacled sprays. The Latin text—also captured by cyanotype, rather than the letterpress-printed technique that was standard in her day—reminds us that, beauty aside, we are in the realm of scientific categorization, capturing natural phenomenon in all their precise glory.

Dictyota stomaria, from Part XI of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, 1849-1850